Key Statistics: Property Location, Size and Exploration Maturity

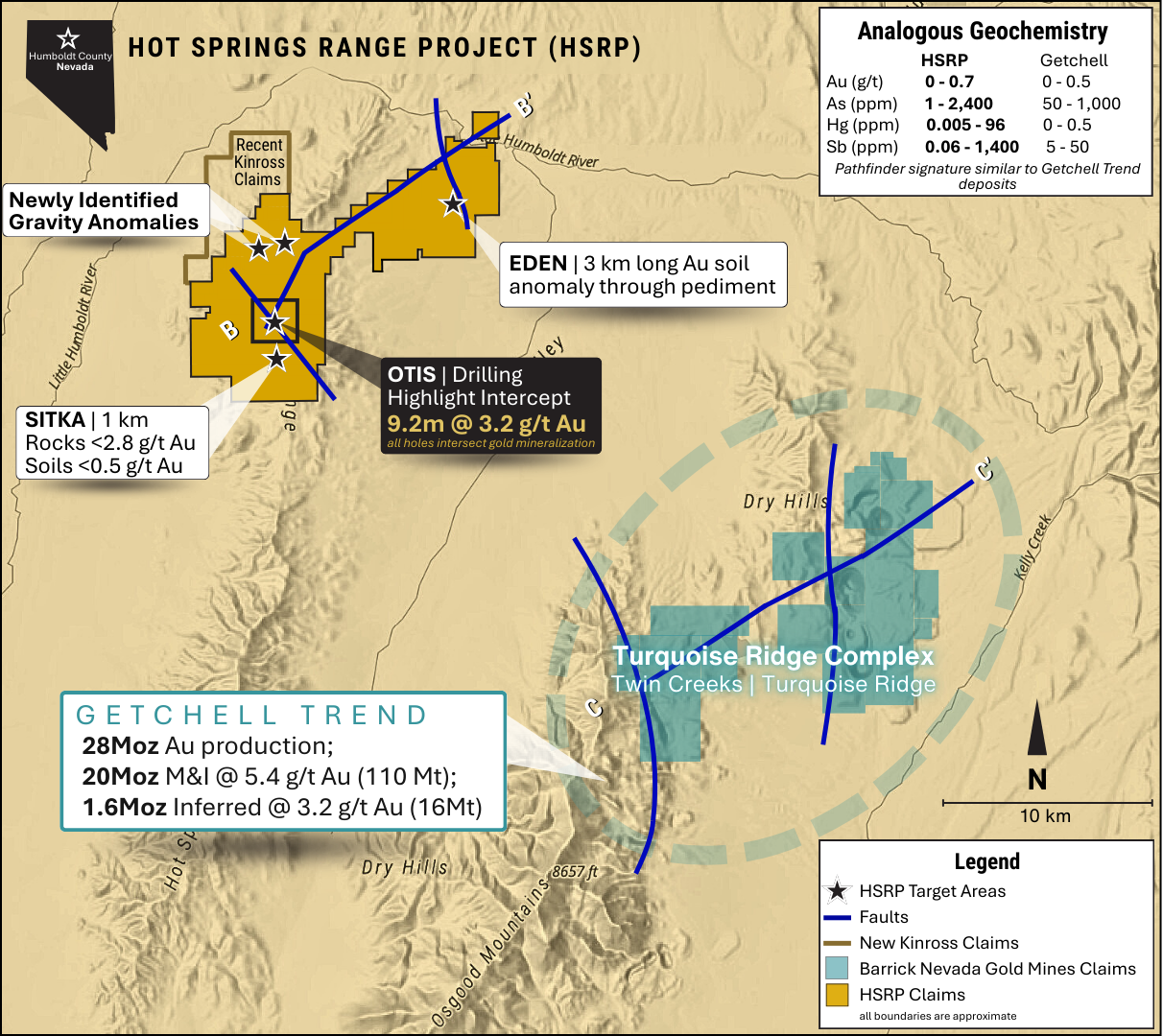

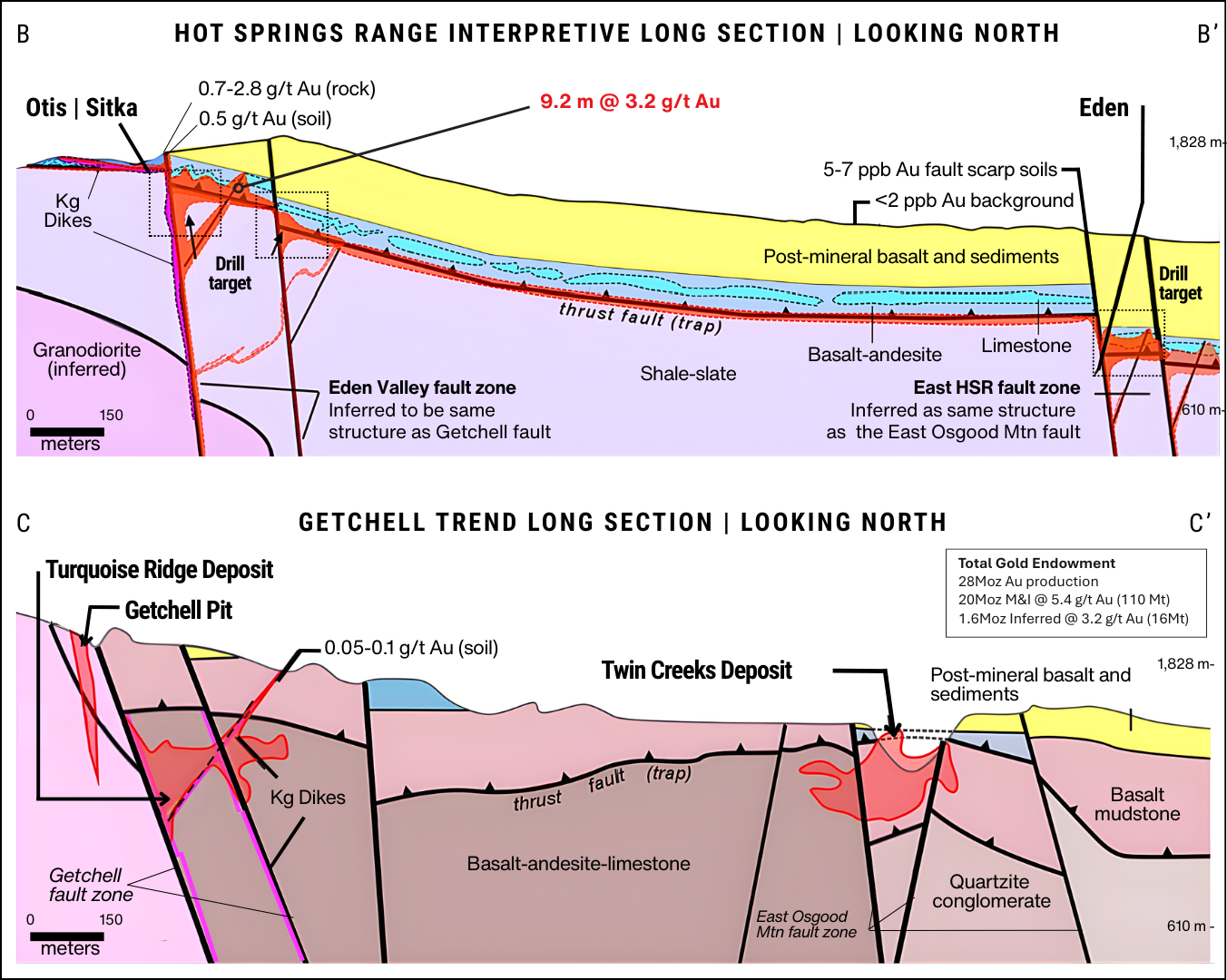

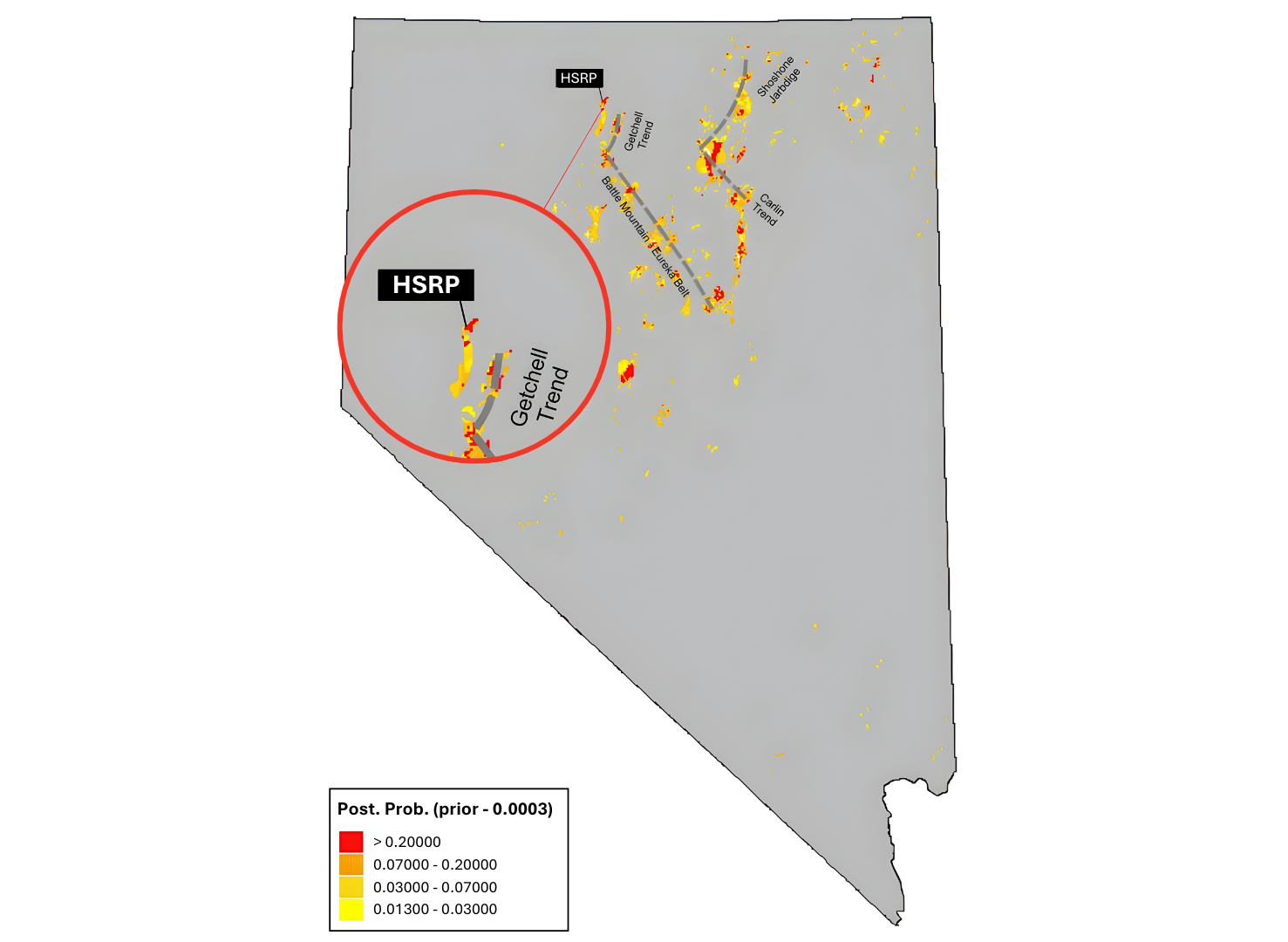

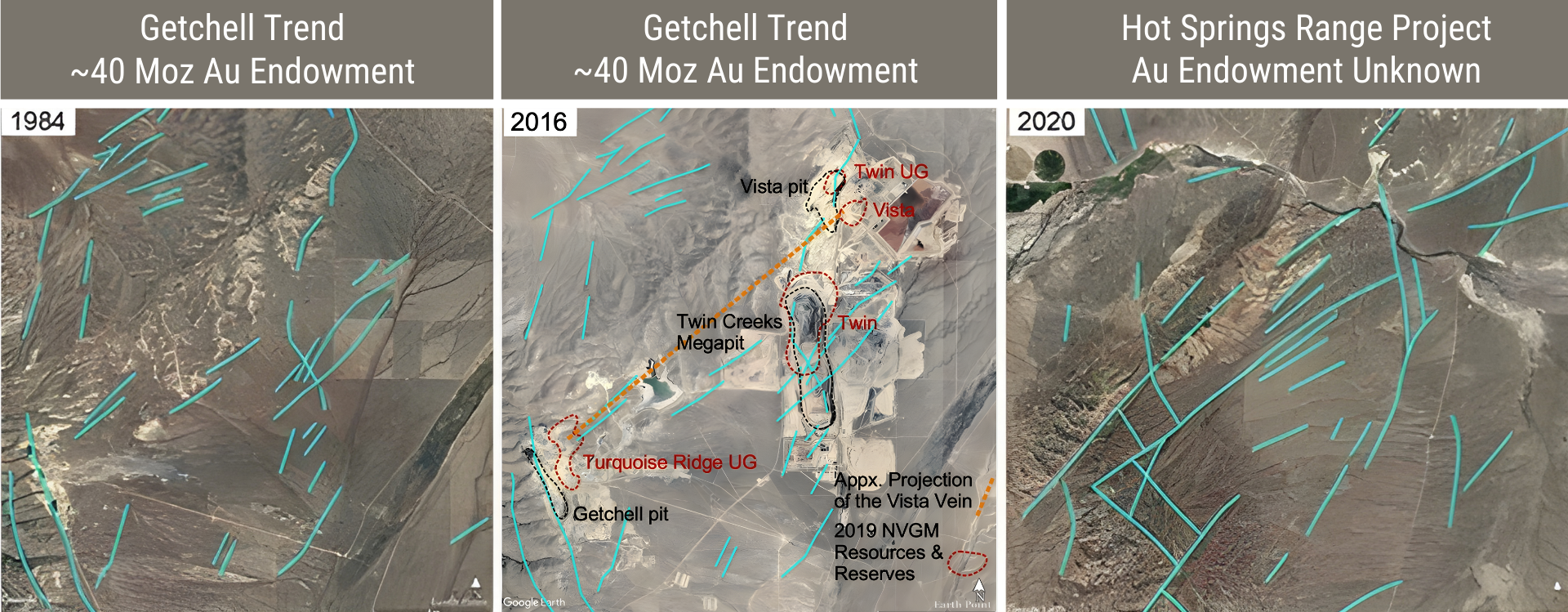

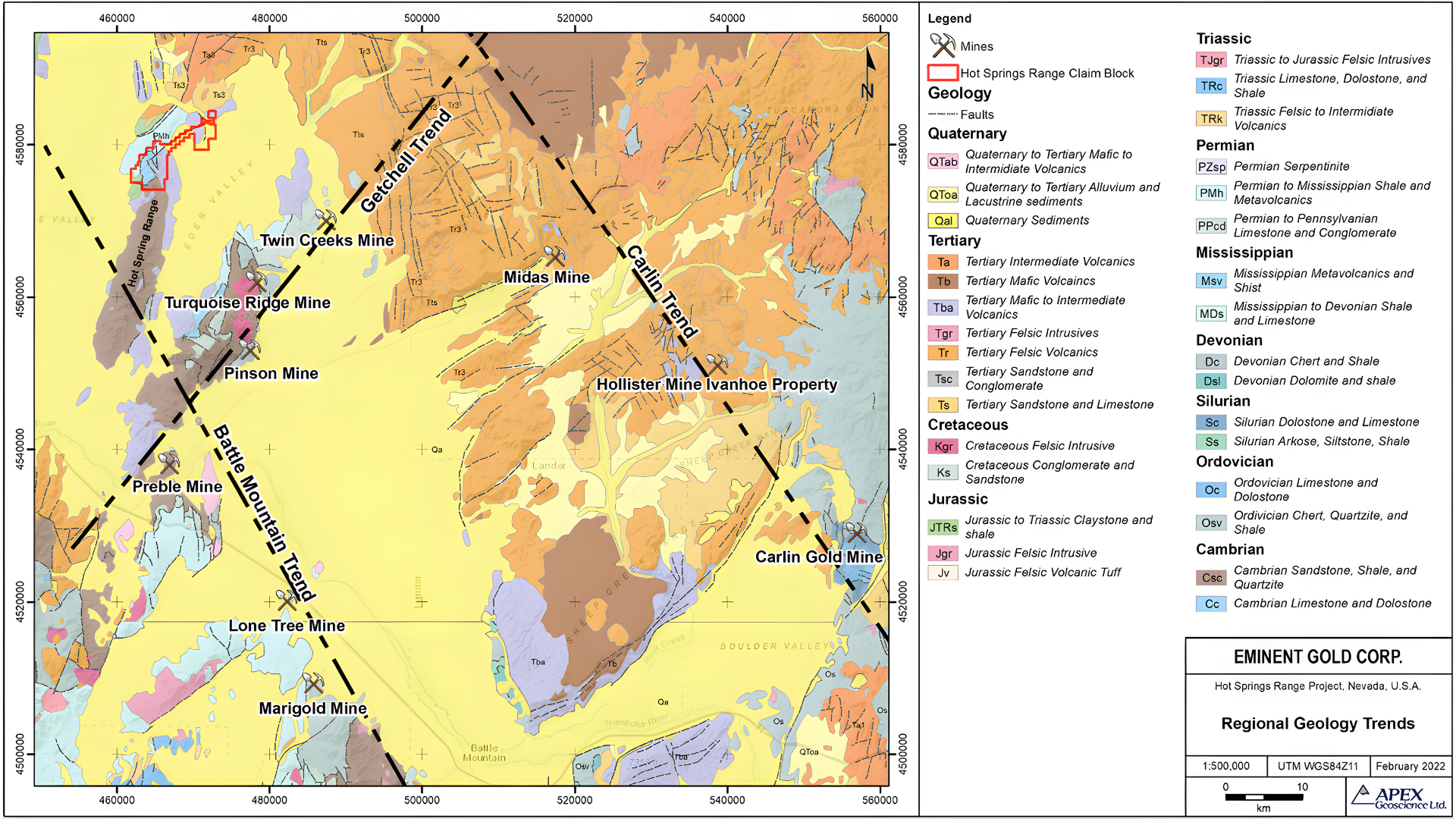

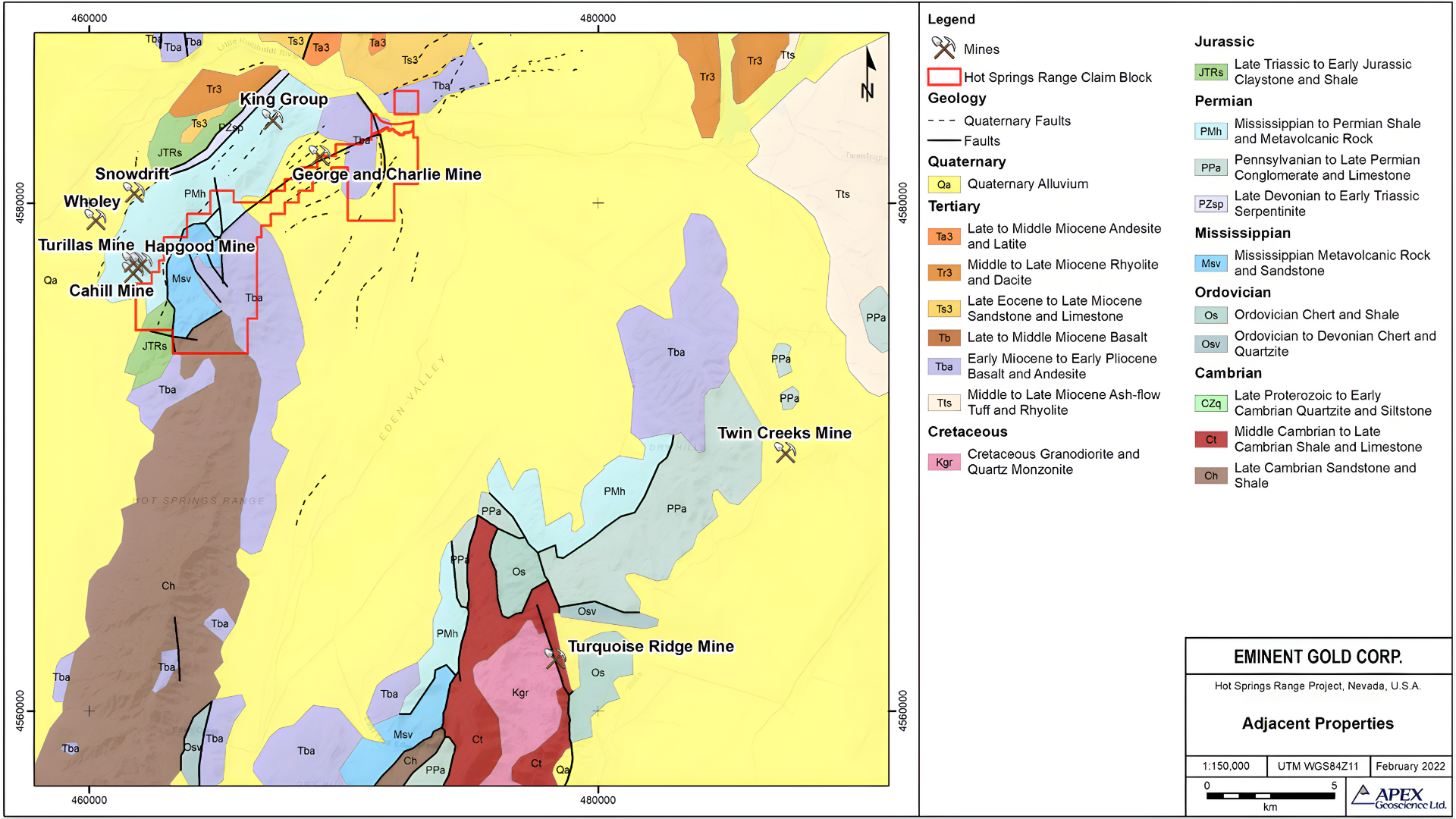

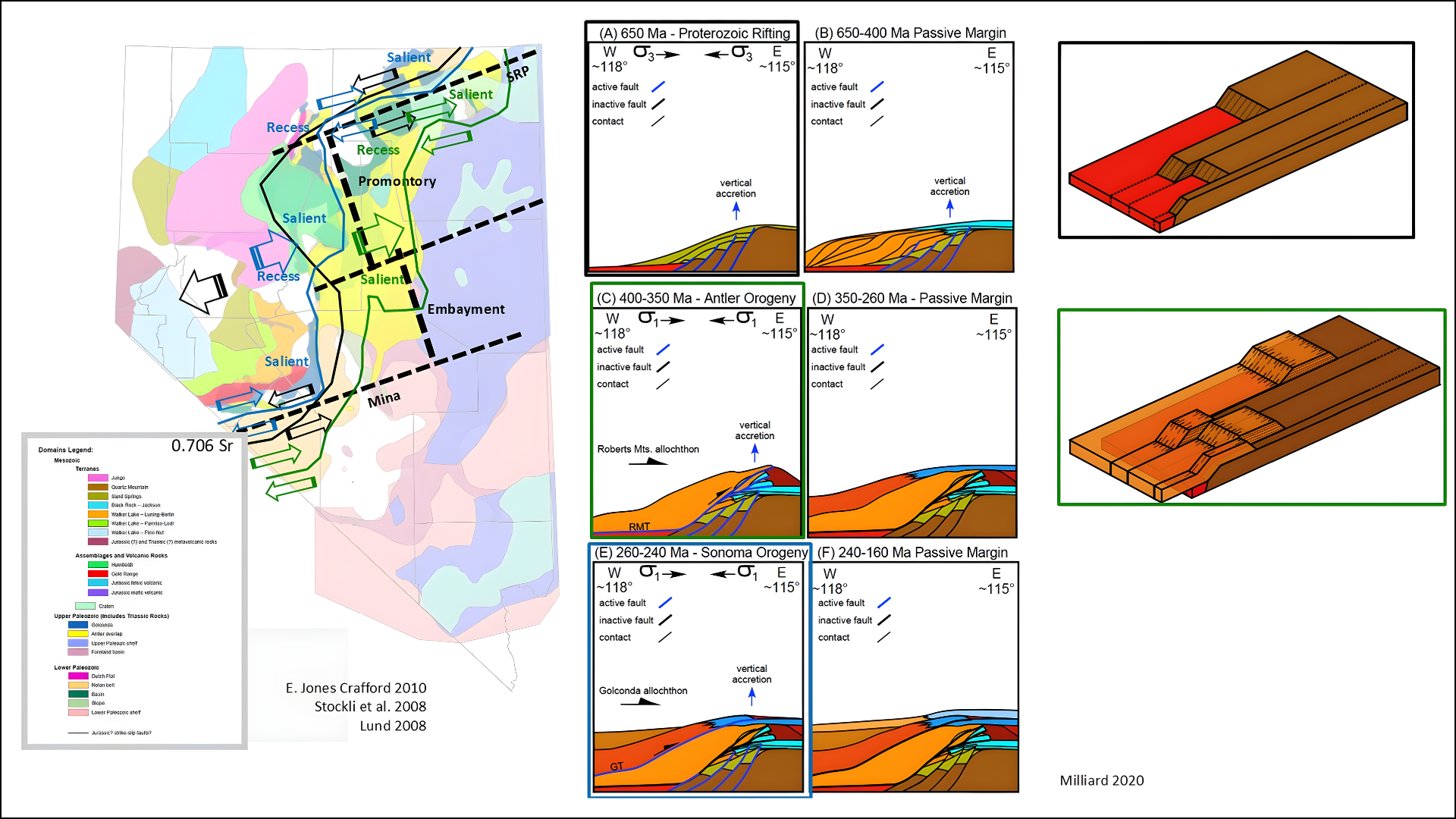

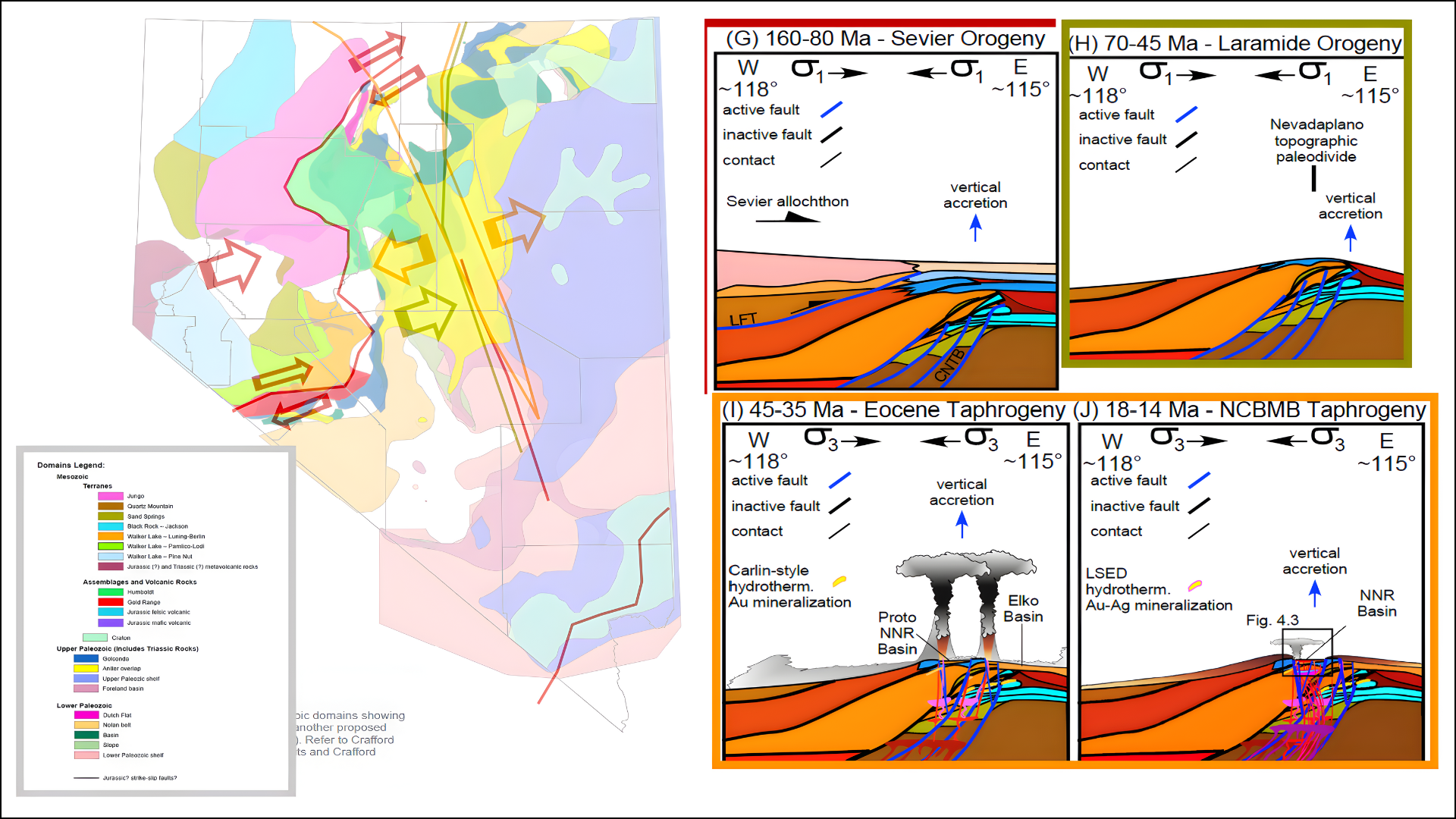

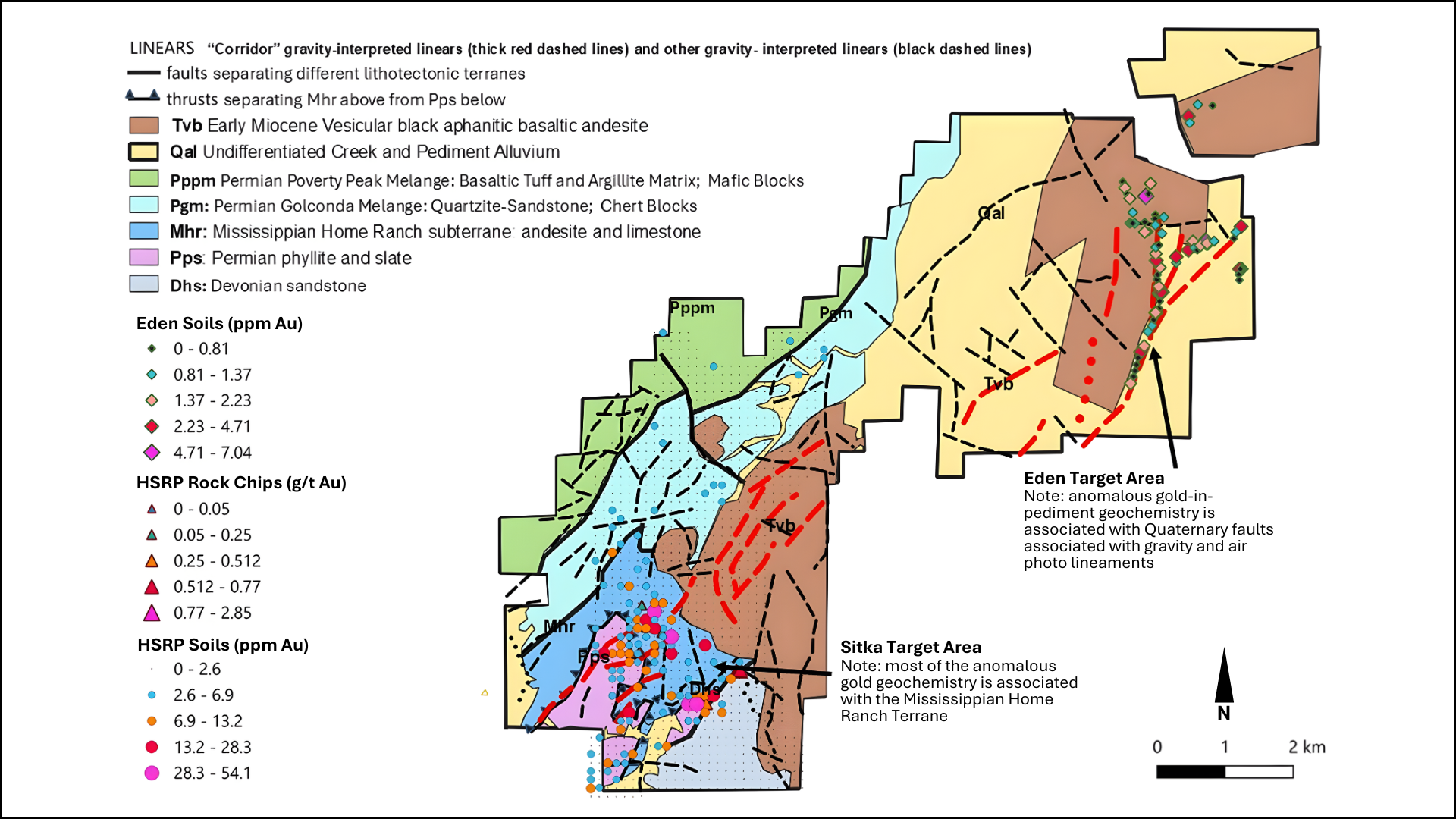

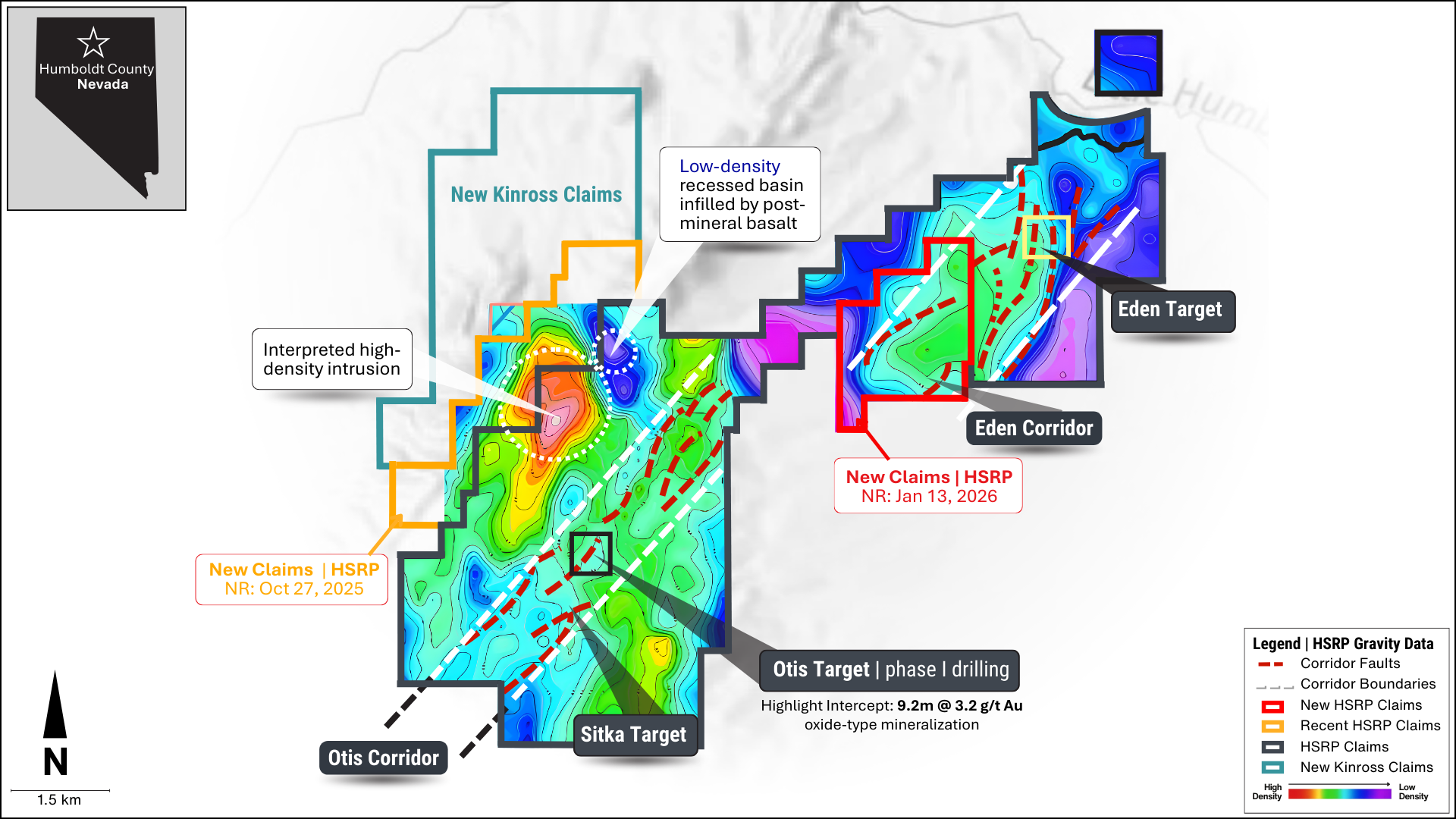

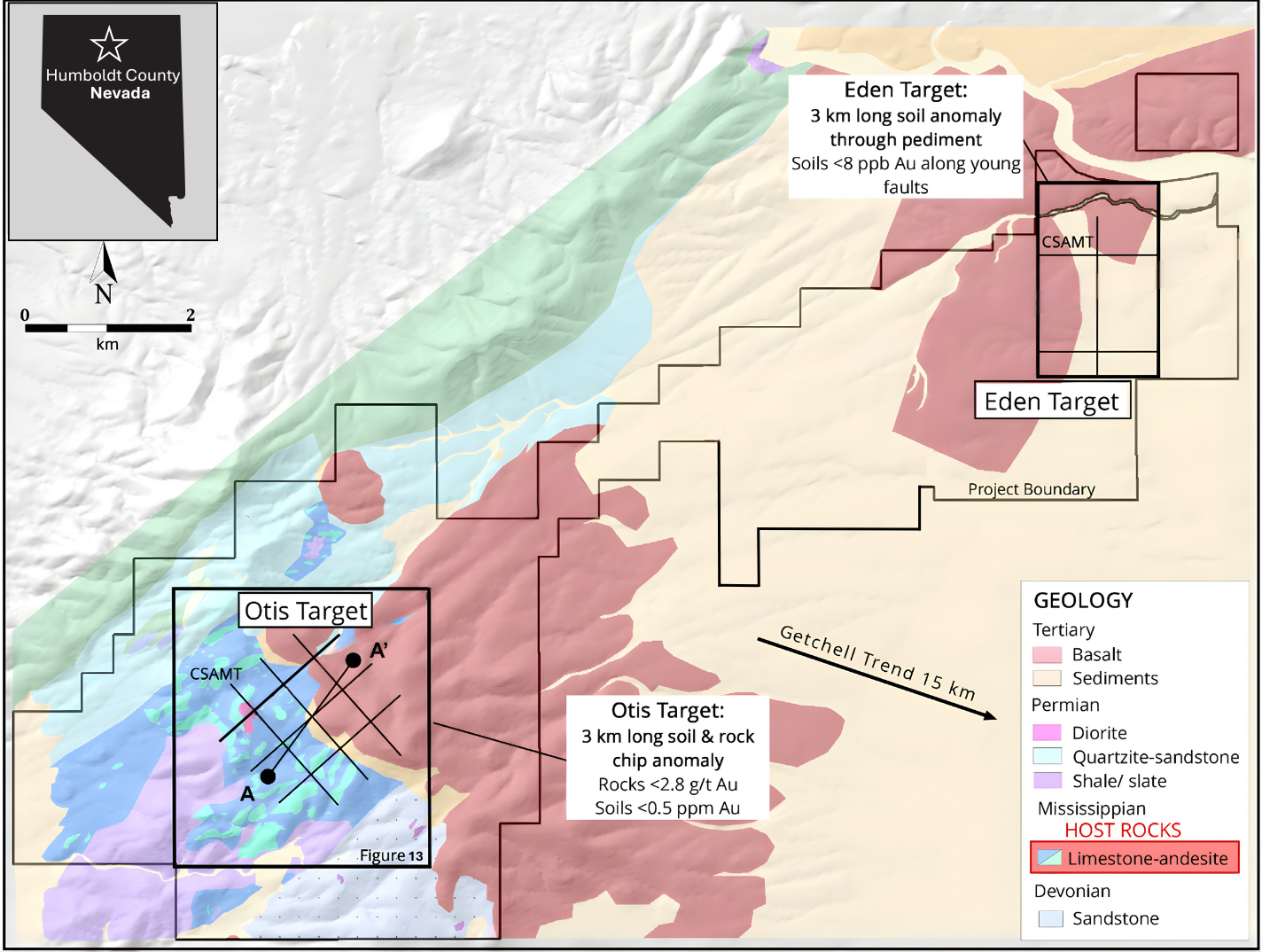

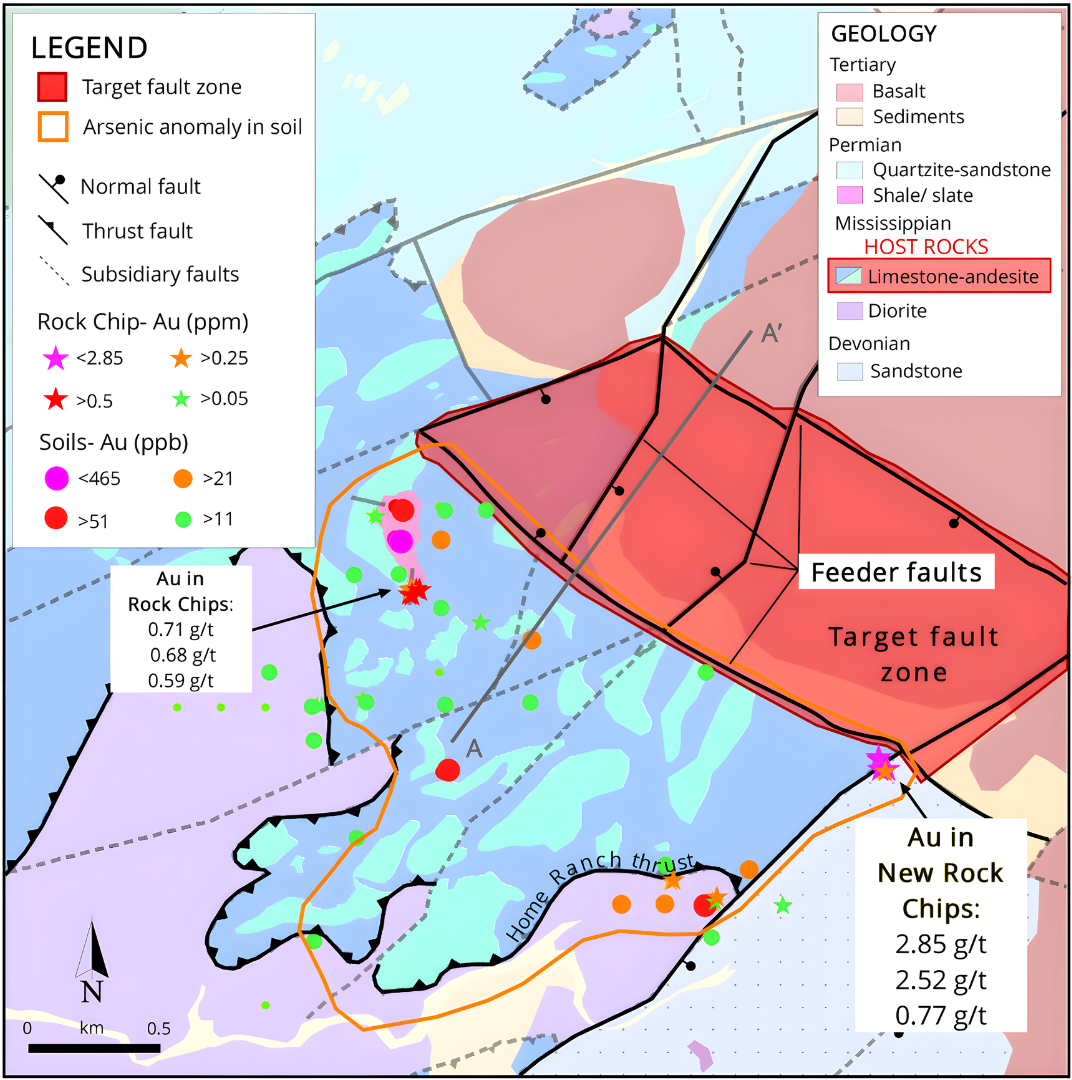

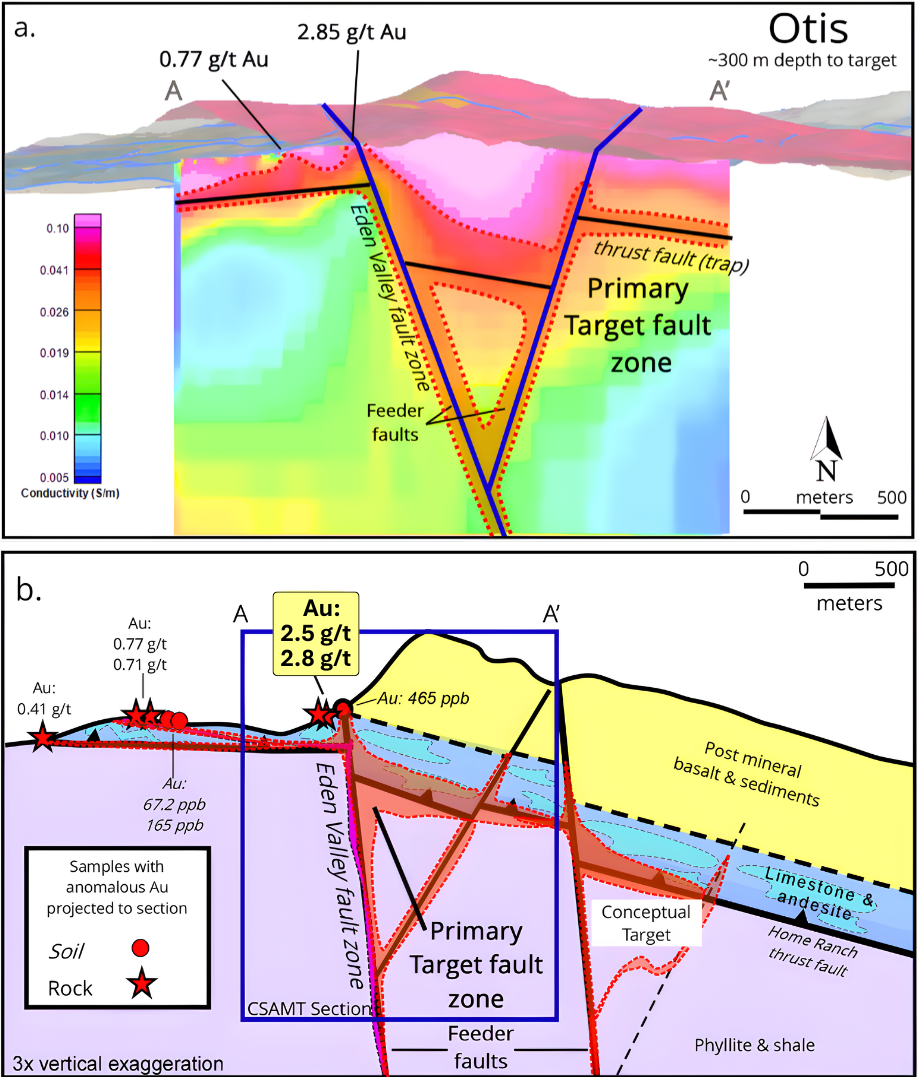

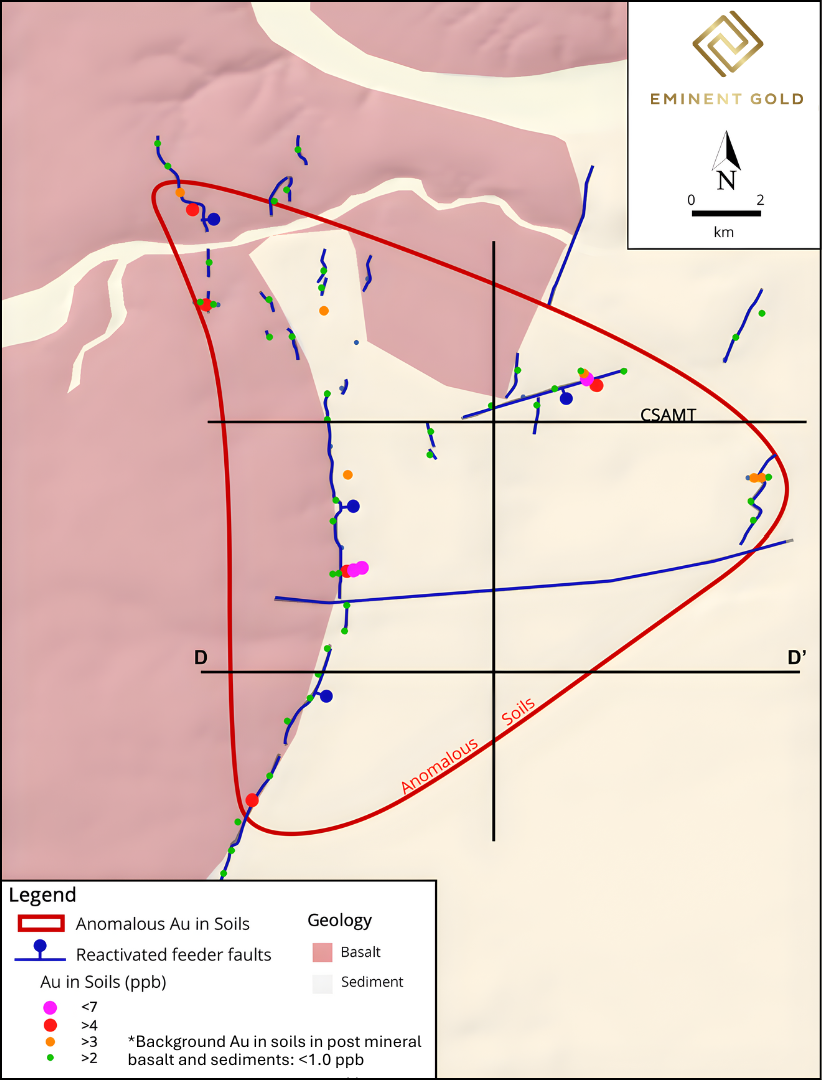

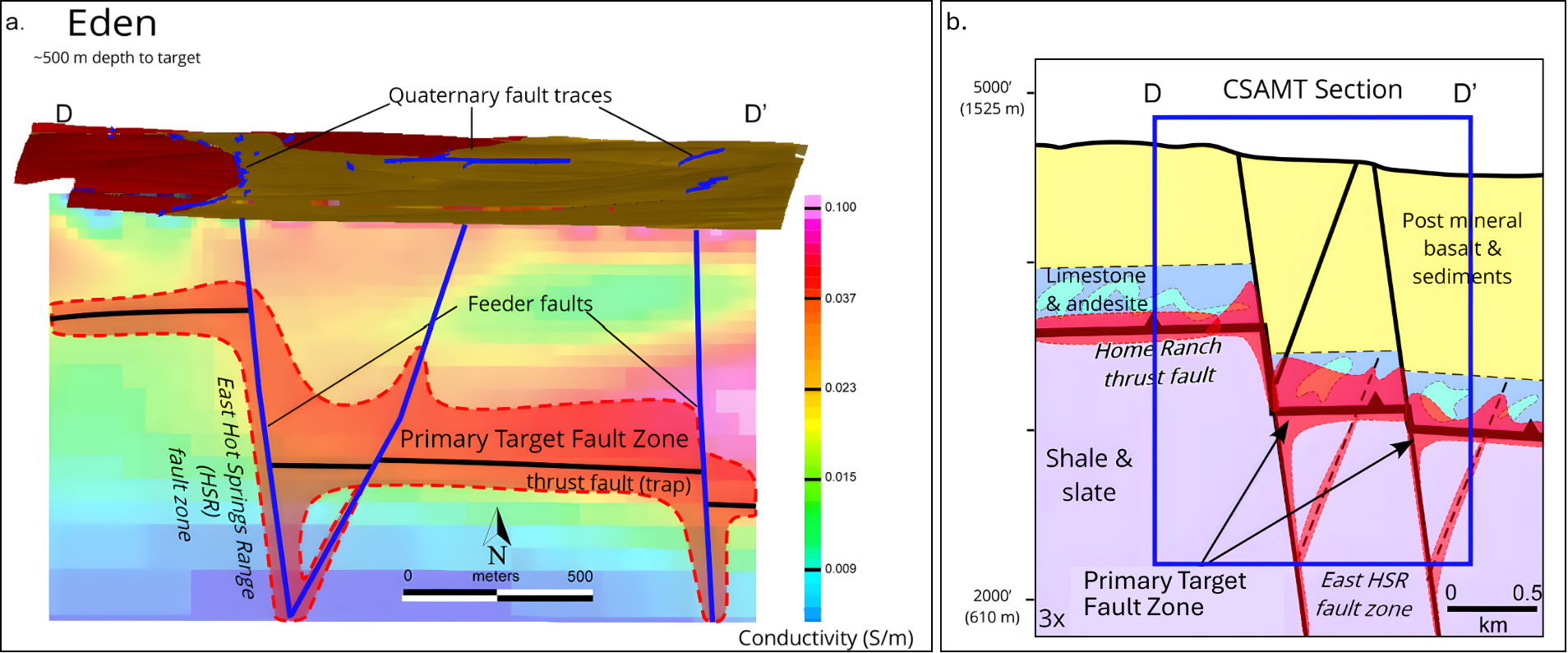

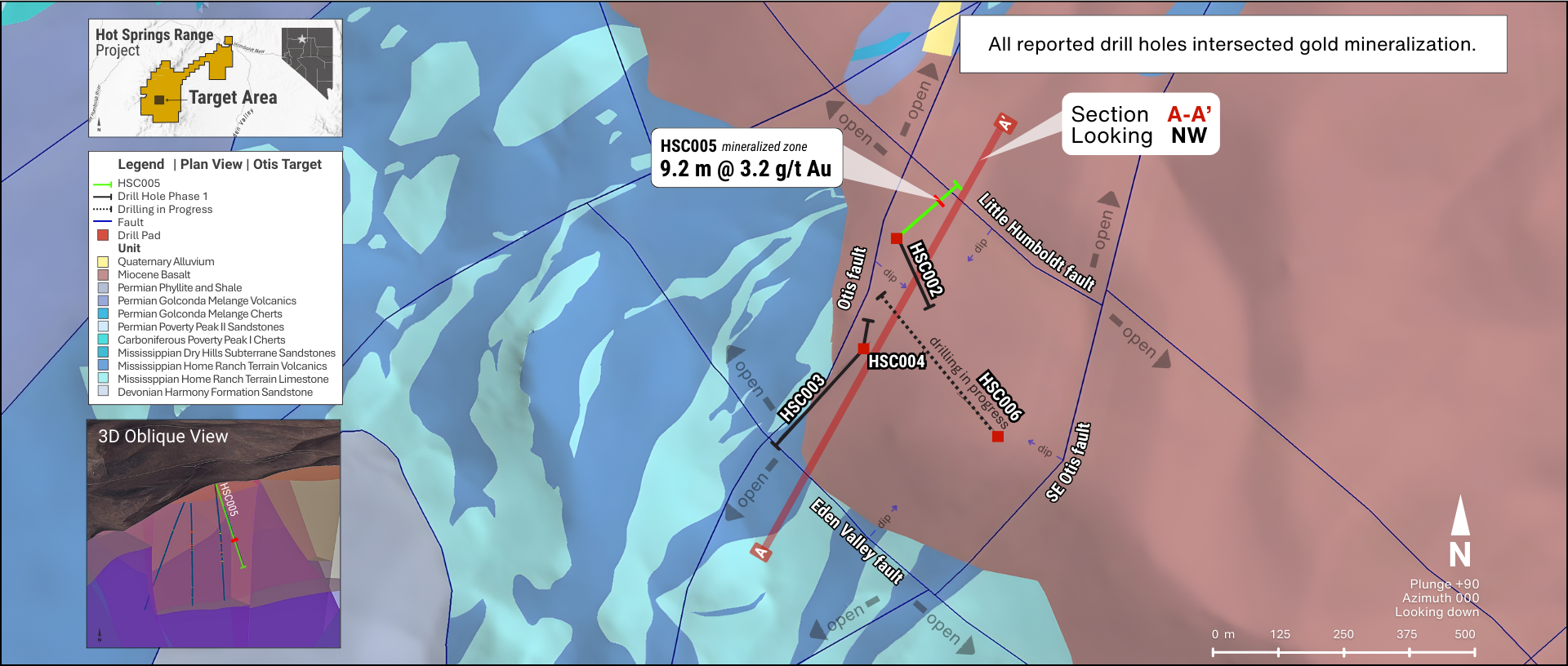

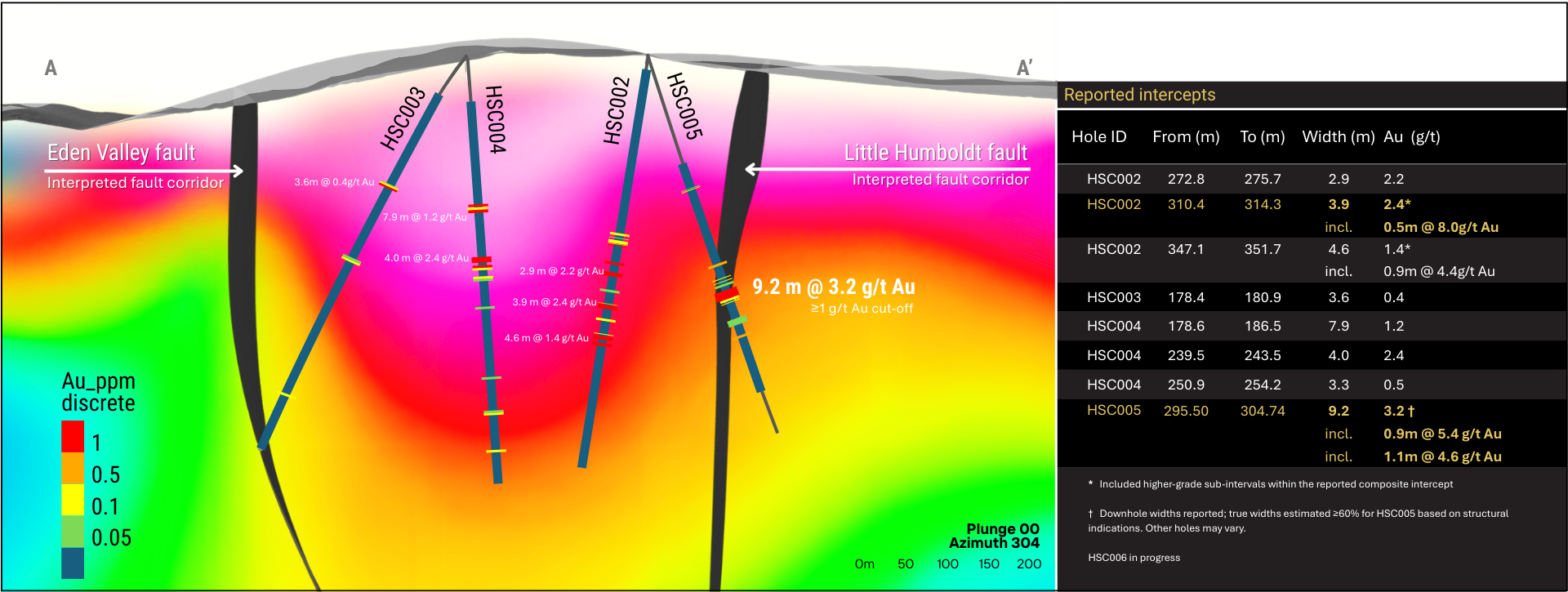

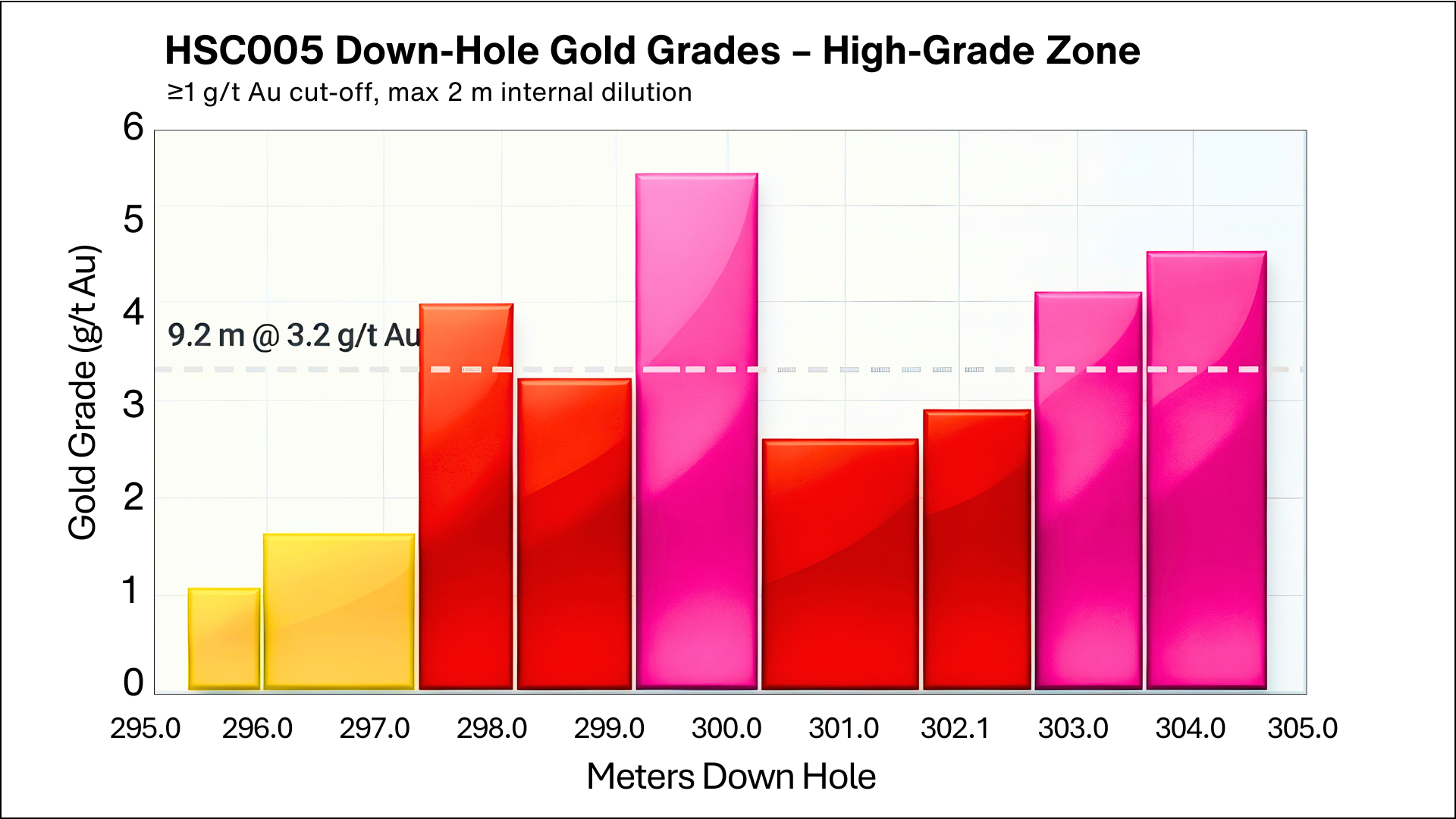

The Hot Springs Range Project (HSRP) area is in northern Humboldt County, Nevada, and comprises 521 federal lode claims on BLM land, totaling 4,311 hectares. It is located 50 km northeast of Winnemucca, NV, and 15 km northwest of Nevada Gold Mines’ Turquoise Ridge Complex in the Getchell Trend. The prospect lies within the Poverty Peak mining district, where minor mercury and antimony production occurred primarily east of HSRP (Bailey and Phoenix, 1944). While there has been limited gold exploration in the area (Master, 2017), there is no evidence that any other company recognized or followed up on the regional concept that led Milliard Geological Consultants (MGC) to stake the property (see Discovery section below). Eminent has completed the option agreement with MGC and now controls the known portion of this emerging Carlin‑style trend through its district‑scale HSRP land package. In May 2025, Kinross became early‑stage investors in Eminent and recently staked additional claims to the north of HSRP.